|

| Pg. 22 |

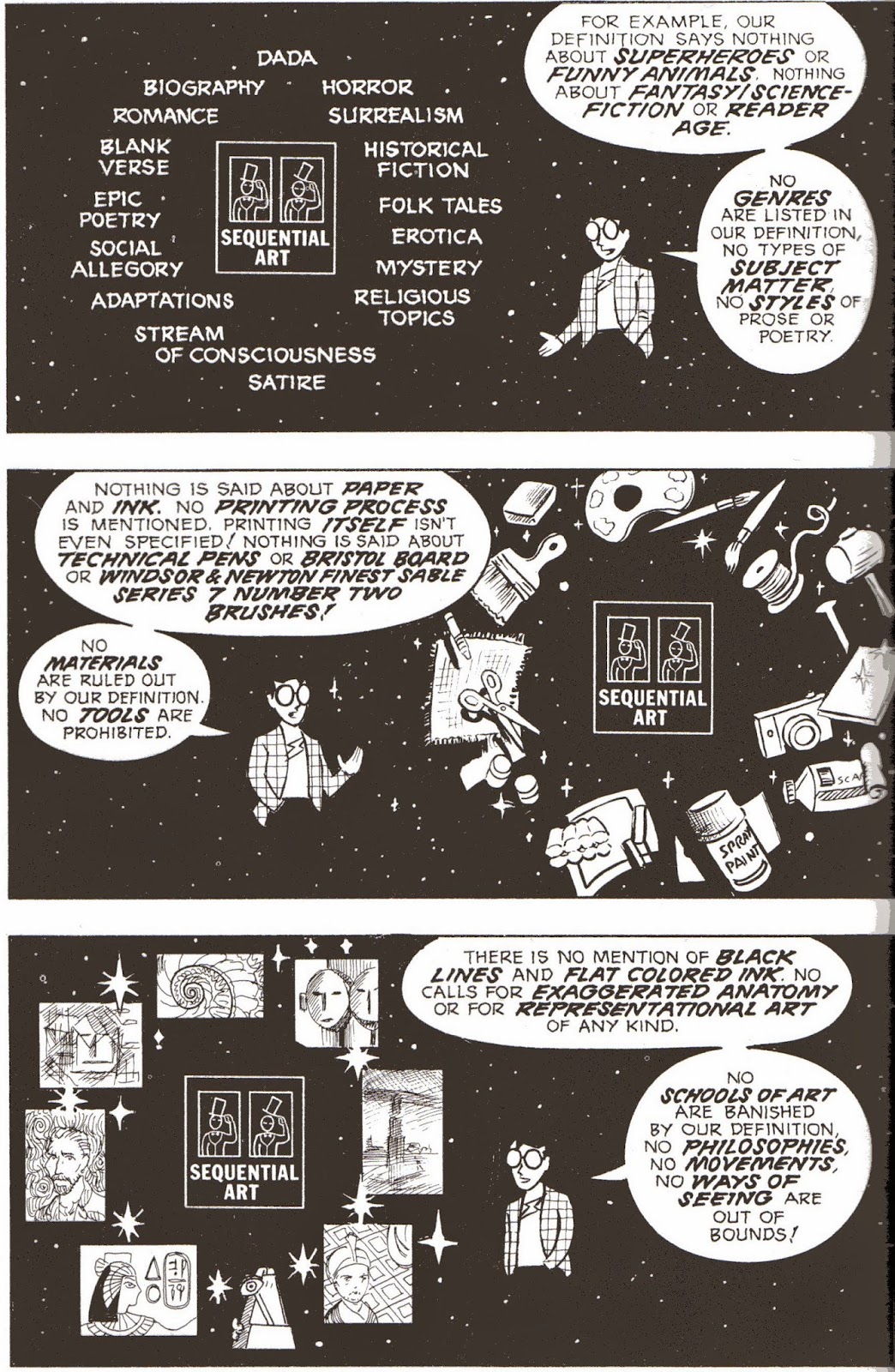

A

comic or graphic novel is not limited in medium or genre. That’s what graphic

novelist Scott McCloud believes as he wrote in the first chapter of his book Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art

that a comic could be done in pencil, ink, painted, sketched with pastels or

charcoal. In addition, a comic’s content is not strictly just about superheroes

or B-movie plots, but can feature a wide range of genres like fantasy,

science-fiction, historical dramas, mystery, epics, social commentary, etc.

There is no limit. Later in his book, McCloud discusses the idea of audience

involvement, the idea of a novelist evoking sympathy to his or her audience

based on the level of detail in their work. In this blog, I will discuss the

ideas McCloud has on comics and how they apply to the graphic novel Fun Home by Alison Bechdel.

|

| Loving father? |

|

| Pg. 18-19 |

Fun Home is a memoir in graphic novel

form that depicts Bechdel growing up in a small town in Pennsylvania. However,

the novel is also a study of Bechdel’s father, her relationship with him, as well

as coming to terms with her sexuality as a lesbian in the wake of his abrupt

death, and how the events have altered her perspective of his character.

McCloud makes a point that to the reader, a cartoon is merely a concept.

McCloud’s comic book avatar declares, “Who I am is irrelevant. . . But if who I

am matters less, maybe what I say will matter more (37). Bechdel’s memoir functions

on a similar principle for I, as a reader, have no idea who Bechdel’s father

was, I have never met him, and I have no chance to meet him now. He exists as a

concept in her novel, the only record of his existence, and it’s up to me as a

reader to judge him based on that.

|

| Seriously. Why should I listen to a three dimensional man? Pg. 36 |

|

| The cartoon man looks way more trustworthy. Pg. 37 |

However, because the only record of Bruce Bechdel is through his daughter, this creates bias in his depiction, a graphic form of the unreliable narrator. Bechdel recalls an oppressive atmosphere growing up because of her father’s obsessive hobby of restoring the family manor and filling it with “beautiful” things. She hated the experience and the environments in the house contrast to other set pieces in the narrative, in which scenes that take place in the manor are highly detailed to emphasize the exquisite beauty her father was obsessively determined to display while to her (and the reader) it was represented as gaudy clutter as opposed to the simplicity in places like her grandmother’s place or the funeral home. McCloud comments, “while most characters were designed simply, to assist in reader-identification––other characters were drawn more realistically in order to objectify them, emphasizing their “otherness” from the reader” (44). As an examination of her father, the detail on him and the manor allows Bechdel to establish the resentment she harbors but also her father’s closeted homosexuality.

In addition, it allows us to perceive him as an alien figure just as Bechdel viewed him while growing up, considering that the cartoon avatar of her late father displays very little emotion, or positive ones at least. Even when Bechdel provides a flashback of her father’s childhood based on a story her grandmother would often retell, he was still stoic.

|

| Pg. 40-41 |

The

idea that the level of detail can evoke an audience sympathy can be rooted in the

theory of the Uncanny Valley, in which the more human attributes we give to a

non-human thing, it becomes off-putting once it’s reached a certain point.

While the principle has its similarities, it still does not function that way.

Nevertheless, we see how Bechdel sees her father, as she uses simplicity to show

peace and happiness and detail creates conflict. In addition, the father is a

concept to us and he is defined by what Bechdel provides us with, including

material that she was not witness to and had to work through speculation.

|

| Bechdel walking in on her father preparing a corpse for a funeral. The nakedness and gore was an uncomfortable memory for her. Pg. 44-45 |

Bechdel, Alison. Fun Home. Boston: Mariner Books, 2006. Print.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper, 1993.

Print.